By Michael Kary, BCCPA Director of Research and Policy

Lately we have seen many concerns, including from media reports and from the BC Office of the Seniors Advocate (OSA), raised about seniors being prescribed too many unnecessary prescription drugs – a practice commonly referred to as polypharmacy. In regards to these concerns, the BC Care Providers Association (BCCPA) has produced a new backgrounder on the issue of polypharmacy, which discusses the use of antipsychotics and anti-depressants in continuing care, as well as the issue of off-label drug use.

As noted in the backgrounder, while the BCCPA agrees with the OSA that polypharmacy among seniors should be minimized as much as possible, it also maintains that the overuse of medications is a significant challenge for all aging adults and not just those living in residential care.

While there is evidence in BC that some residents in long term care are overly medicated there is less supporting evidence, however, that this is primarily attributable to individual care homes. In particular, the literature outlines that polypharmacy among residents in long-term care are largely a result of factors relating to physician prescribing practices.[i] Furthermore, pharmacists have a particularly critical role to play in ensuring that medications prescribed to seniors are appropriate and safe.[ii] Nonetheless, all health care providers have a role in dealing with polypharmacy and ensuring appropriate prescribing practices.

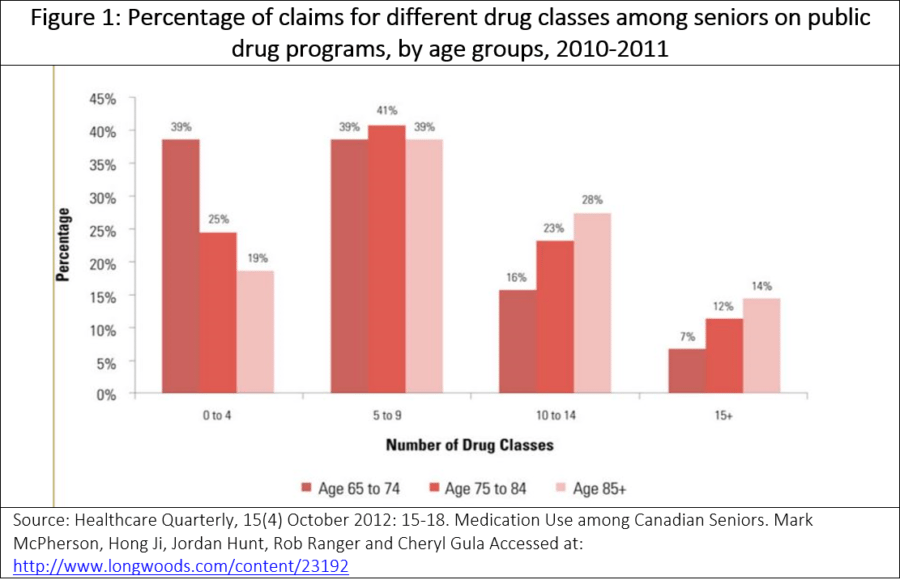

According to one study from 2012, roughly 69%, or 1.8 million of all seniors in Canada are taking five or more drugs with nearly 10% (293,000 seniors) taking 15 or more (see Figure 1). This increases with age, with those who were 85 or older being twice as likely to take at least 15 drug classes compared with those in the 65–74 age group.[iii] In 2012, nearly 40 percent of seniors were taking 10 or more drugs.

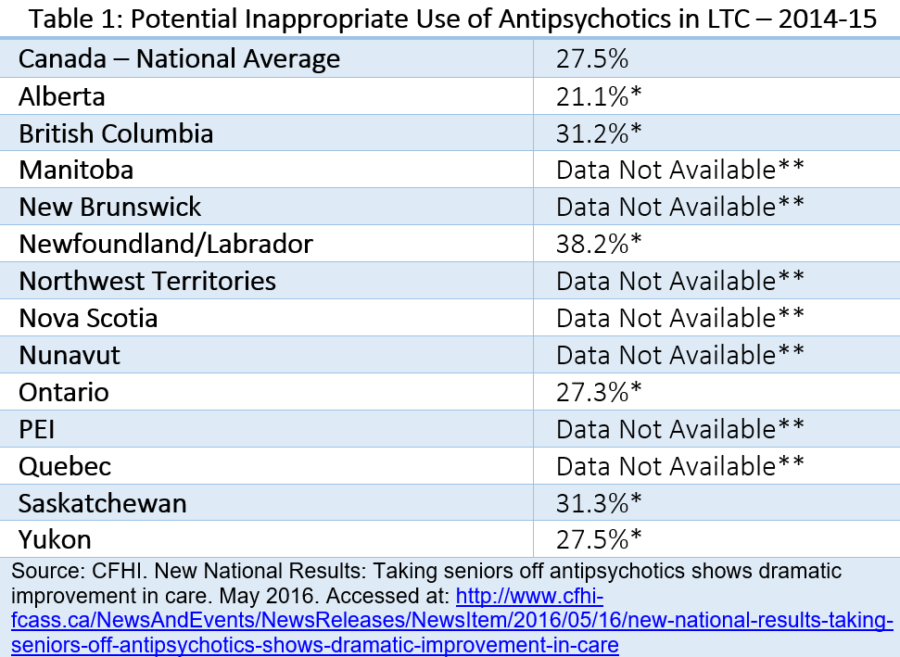

Evidence from numerous studies also shows that many medications prescribed to elderly patients are inappropriate in that they introduce a significant risk for an adverse drug events when there is evidence that alternative medication may be equally or more effective. In primary care, for example, one study notes approximately 1 in 5 prescriptions issued for older adults is inappropriate.[v] According to the most recent figures from Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), 31.2 percent of long-term care residents in BC, for example, are inappropriately prescribed antipsychotics medication, which is slightly higher than Canadian average (see table 1 below).[vi]

Although it may be appropriate for some seniors to take a number of drugs, the use of multiple medications, increases the risks of drug interactions and side effects. In particular, polypharmacy increases the risk for adverse drug reactions (ADRs), adverse drug events (ADEs), falls, hospitalization, mortality, and other adverse health outcomes among seniors. According to one study, 13% of seniors taking 5 or more prescription medications experience ADEs that required medical attention, compared with 6% of those taking 1 or 2 drugs.[iv]

Residential care providers and family members may have some influence over the prescribing practices of physicians, but it is important to note that care operators have been active in attempting to reduce anti-psychotic drug use among seniors, including working collaboratively with physicians. This includes the Doctors of BC and the provincial government Poly Pharmacy Risk Reduction project to reduce the amount of medication prescribed to seniors. This initiative, which started in eight care homes and is being expanded province-wide involves a multidisciplinary approach including physicians, pharmacists, care home staff, the resident and family members collaborating to design processes and implement strategies for polypharmacy risk reduction for each resident in care. [vii]

Some of other BC initiatives, focusing on antipsychotic drug use, include the development of a BCCPA Best Practices Guide for Safely Reducing Anti-Psychotic Drug Use in Residential Care;[viii] participation in the provincial government’s Call for Less Antipsychotics in Residential Care (CLeAR) initiative;[ix] and working with the BC Health Ministry to develop and implement a province-wide guideline for antipsychotic drug use in residential care homes.[x]

While these and other initiatives have helped reduce anti-psychotic use, unfortunately they have not been the focus of reports including those from the BC OSA.[xi] As outlined in the Backgrounder, the BCCPA recommends the OSA should consider focusing much of its future work on developing reports highlighting best practices for seniors’ care (including home and residential care) that are being undertaken in BC and other jurisdictions. One such example could be a report on initiatives or practices under way in continuing care to reduce polypharmacy particularly antipsychotic drug use. Along with being consistent with the mandate of the OSA, the BCCPA believes such best practice reports – including on polypharmacy – would provide a valuable resource for those in the continuing care sector to better educate and train health professionals as well as improve overall seniors’ care.

Another best practice to reduce level of antipsychotic use that should be explored in BC is Behavioral Supports Ontario (BSO), which involves coordinated care teams and training to better address seniors with challenging or responsive behaviors.[xii] In its 2016 budget, the Ontario government announced it would invest an additional $10 million annually in BSO to help long-term care home residents with dementia and other complex behaviors.[xiii] In particular, the BCCPA would support funding for a similar BSO type program which could provide training, education and resources to improve dementia care in BC. Another example of a best practice is seen by recent initiatives from the CFHI including its collaborative partnership with the New Brunswick Association of Nursing Homes (NBANH).[xiv] A national program to reduce antipsychotics, as advocated recently by the CFHI, is something that also merits consideration.

Another best practice to reduce level of antipsychotic use that should be explored in BC is Behavioral Supports Ontario (BSO), which involves coordinated care teams and training to better address seniors with challenging or responsive behaviors.[xii] In its 2016 budget, the Ontario government announced it would invest an additional $10 million annually in BSO to help long-term care home residents with dementia and other complex behaviors.[xiii] In particular, the BCCPA would support funding for a similar BSO type program which could provide training, education and resources to improve dementia care in BC. Another example of a best practice is seen by recent initiatives from the CFHI including its collaborative partnership with the New Brunswick Association of Nursing Homes (NBANH).[xiv] A national program to reduce antipsychotics, as advocated recently by the CFHI, is something that also merits consideration.

One of the other challenges related to polypharmacy, including for anti-psychotic and anti-depressants, is off-label drug use.[xv] As outlined in the BCCPA backgrounder, to better address the issue of the off label use of drugs, it will require the better documentation in resident health records. Likewise, there needs to be a better understanding of what off-label prescribing is safe, including establishing an efficient and effective way to monitor the adverse reactions of drugs that are prescribed off-label. As also discussed in the BCCPA backgrounder, ensuring proper prescribing and documentation of medications, including outlining reasons for usage is properly documented, is also critical. For example, if a diagnosis of depression is what necessitates the prescription of anti-depressants, this should be clearly documented.

Finally, while there have been concerns raised about the overuse of anti-depressants among seniors in residential care, further research on this is required to determine if this is indeed the case as well as the overall extent. In particular, attempts should be undertaken, where possible, to ensure the appropriate use of antidepressants in conjunction with other therapies, including activities such as regular exercise. As outlined in the backgrounder, areas the BCCPA would support further to ensure the appropriate use of anti-depressants include: 1) Increasing funding or resources for activities to improve one’s physical or mental well-being in residential care; 2) Increased training for psychologists and other mental health professionals to work with older adults; and 3) Destigmatizing psychological care.

Taken together the BCCPA believes the issue of polypharmacy is a serious one that needs to be addressed, not just among residents in long-term care, but among seniors more generally. As such coordinated action should be undertaken both by government and care providers to minimize, where appropriate, the use of polypharmacy and in particular the use of anti-psychotics. The BCCPA and its members will continue efforts to ensure more appropriate prescribing and documenting of prescription medication in order to address the issues of off-label drug use, in particular for anti-psychotics.

END NOTES

[i] Deprescribing medication for frail elderly patients in nursing homes: A survey of Vancouver family physicians. BCMJ, Vol. 56, No. 9, November 2014, page(s) 436-44. Accessed at: http://www.bcmj.org/articles/deprescribing-medication-frail-elderly-patients-nursing-homes-survey-vancouver-family-physi

[ii] Canadian Pharmacists Association. The Translator. Fall 2013, Volume 7, Issue 3. Accessed at: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/education-practice-resources/Translator2013V7-3EN.pdf

[iii] Healthcare Quarterly, 15(4) October 2012: 15-18. Medication Use among Canadian Seniors. Mark McPherson, Hong Ji, Jordan Hunt, Rob Ranger and Cheryl Gula Accessed at: http://www.longwoods.com/content/23192

[iv] Deprescribing in Clinical Practice: Reducing Polypharmacy in Older Patients Linda Brookes. November 26, 2013. Accessed at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/814861_2.

[v] Deprescribing in Clinical Practice: Reducing Polypharmacy in Older Patients Linda Brookes. November 26, 2013. Accessed at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/814861_2.

[vi] CFHI. New National Results: Taking seniors off antipsychotics shows dramatic improvement in care. Accessed at: http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/NewsAndEvents/NewsReleases/NewsItem/2016/05/16/new-national-results-taking-seniors-off-antipsychotics-shows-dramatic-improvement-in-care

[vii] Doctors of BC. Seniors and Medication. April 8, 2015. Accessed at: https://www.doctorsofbc.ca/hot-health-topics/seniors-and-medication

[viii] BCCPA. Best Practices Guide for Safely Reducing Anti-Psychotic Drug Use in Residential Care (2013) https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/Anti-Psychotics-Guide-hr-06-05-13.pdf

[ix] BC Patient and Safety Quality Council. CLeAR Initiative. See https://bcpsqc.ca/clinical-improvement/clear/

[x] In October 2012 the Ministry of Health released the British Columbia Best Practice Guideline for Accommodating and Managing Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Residential Care. The main objectives of this guideline are to improve the quality of care of dementia patients in residential care, improve family member and caregiver engagement in care, focus on appropriate use of antipsychotics in BPSD patients in care homes and build systemic capacity for better supporting assessment and care of patients with BPSD.

[xi] BC Office of the Seniors Advocate. Residential Care Facilities: Quick Facts Directory. January 2016. http://www.seniorsadvocatebc.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/05/BC-Residential-Care-Quick-Facts-Directory-May-2016.pdf.

[xii] BCCPA. Op-ed: Reducing Resident on Resident Aggression in British Columbia. January 5, 2016. Accessed at: https://bccare.ca/op-ed-reducing-resident-on-resident-aggression-in-british-columbia/.

[xiii] Transforming Health Care. Ontario Government. February 25, 2016. Accessed at http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/budget/ontariobudgets/2016/bk8.html

[xiv] Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI). CFHI and Nursing Homes Join Forces to Improve Dementia Care In New Brunswick. May 17, 2016. Accessed at: http://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/cfhi-and-nursing-homes-join-forces-to-improve-dementia-care-in-new-brunswick-579780731.html

[xv] For the purposes of the backgrounder, off label drug use is defined as the use of pharmaceutical drugs for an unapproved indication or in an unapproved age group, dosage or route of https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/medcare-img22.jpgistration.