Almost on a daily basis we hear stories about a senior who is languishing in a hospital who could be better cared for in another care setting such as their own home or within residential care. Many of us may even know of such a person. When a person is occupying an acute care bed and unable to access home and community care services they are referred to as Alternate Level of Care (ALC) or bed blockers.

Currently, approximately 14% of Canadian hospital beds are filled with patients (85% of which are seniors) who are ready to be discharged but for whom there is no appropriate place to go. Over a single year, these patients’ use of acute hospital beds exceeds 2.4 million days, which equates to over 7,500 acute care beds each day.[i]

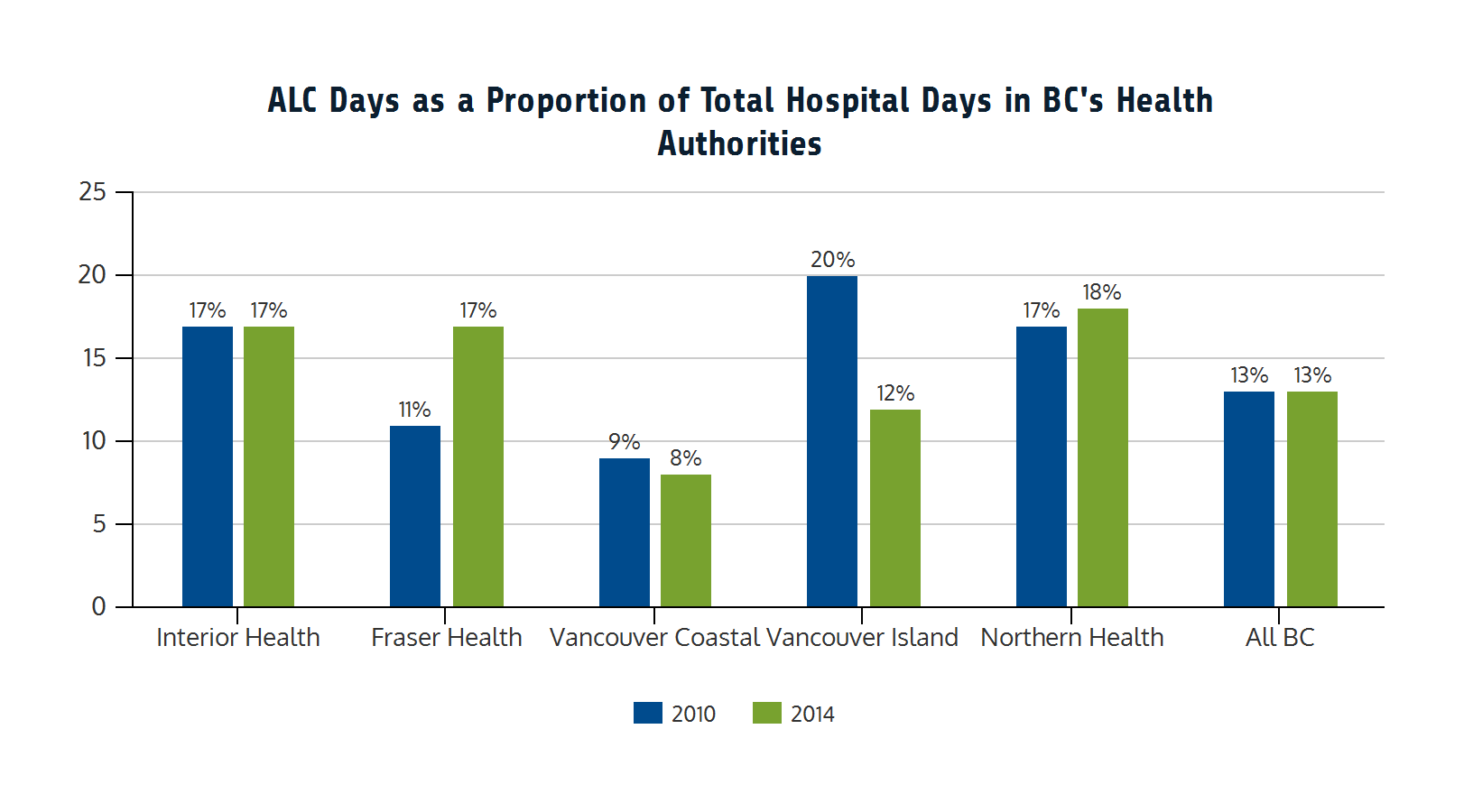

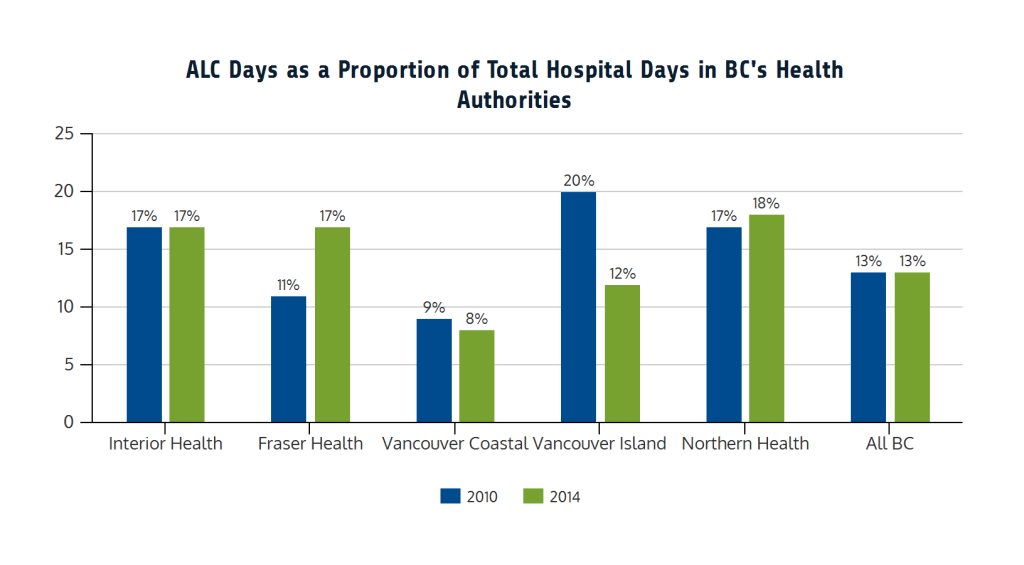

As outlined in a 2015 BC Care Providers Association (BCCPA) paper, there were over 400,000 reported ALC days in BC in 2014/15, accounting for 13% of total hospital days across the five regional health authorities (see figure below). There were also significant variations across the Health Authorities from a low of 8% in Vancouver Coastal to 18.1% in Northern Health.[ii] BC’s health authorities also report that about one-half of ALC patients are awaiting discharge into long-term care, while others are waiting for home care, assisted living, rehabilitation or are residing in acute care due to an inefficient transfer processes.[iii]

As outlined in the BCCPA paper, a 50% reduction in ALC days could generate significant cost savings to the health system. For example, assuming 50% of ALC days could be reduced by caring for patients in residential care homes (average daily cost of $200) instead of in a hospital (average daily cost of $1,200) it could generate over $200 million in annual cost savings.[iv]

The problem of ALC beds not only create fiscal challenges, but quality of care and access issues as well. The Wait Time Alliance (WTA), for example, has noted that the ALC issue represents the single biggest challenge to improving wait times across the health care system.[v] These wait times and access issues have been well documented. In 2012, for example, it was reported that 461,000 Canadians were not getting the home care they thought they required, while wait times for access to long-term care in Canada also ranged anywhere from 27 to 230 days.[vi]

There are many reasons for the high rates of ALC patients, including the lack of appropriate community supports to prevent hospitalizations, as well as to return patients to a more appropriate setting after they receive hospital care.[vii] The ALC issue is also one that is closely tied to dementia, a common diagnosis among ALC patients. In particular, a dementia diagnosis often results in at least once instance of hospitalization and escalates ALC rates when persons with dementia have other chronic diseases (i.e. 90% of community-dwelling persons with dementia have two or more chronic diseases). A study in New Brunswick found that one third of the beds in two hospitals were occupied by ALC patients, of whom 63% had been diagnosed with dementia. It also found their mean length of stay was 380 days, with 86% of these patients waiting for a bed in a long-term care home while their health declined.[viii]

As outlined by the WTA, adequate attention to seniors’ care – such as having the necessary health human resources, treating seniors where they live thereby preventing unnecessary emergency department visits and hospitalizations, as well as collaborative care models – are key to reducing the numbers of ALC patients [ix] In particular, one critical area for improving the ALC situation is the better reporting of such data. The UK’s National Health Service, for example, reports monthly ALC rates as delayed transfers of care including outlining the causes of delay by region and facility.[x] This could also be one area for the BC Office of the Seniors Advocate (OSA) to report on. Although the BC OSA released their first Monitoring Seniors Services report in January 2016 highlighting data on various key seniors’ services including health care it does not address ALC rates or keeping seniors out of hospitals.[xi]

The BCCPA believes adopting this type of comprehensive public reporting across Canada, including British Columbia, would greatly assist efforts to tackle the ALC issue. Along with reinvestments in continuing care and the development of new collaborative care models, the BCCPA has advocated that the Health Authorities and Ministry of Health better utilize the existing capacity and expertise amongst non-government care operators – this includes developing strategies to reduce ALC beds and offset acute care pressures.

The BCCPA has recommended the creation of a new publicly accessible online registry to report on ALC and vacant residential care beds, as well as the use of current vacant beds within residential care homes, assisted living units and home support to reduce acute care pressures. In regards to the latter area, well-designed home care and home support services with quick response capabilities can also be effective in getting seniors out of acute care. Vancouver Island Health’s Quick Response Team, for example, provides crisis intervention at home to eligible clients when required, aimed at preventing avoidable hospital admission, provide crisis intervention at home and facilitate early hospital discharge.

Most people can agree that seniors should not be languishing in an acute care hospital when it would be better from a quality of care perspective for that person to be in a more appropriate care setting within the community. While improving the quality of information is one step that needs to be undertaken in order to reduce ALC days; it will also be imperative to establish the appropriate supports in the community and invest appropriately in continuing care. Unless action is taken, the ALC problem will likely worsen, as it is projected that with an aging population more than 25% of Canadians will be older than 65 by 2036. The time for action is now.[xii]

END NOTES

[i] Exploring alternative level of care (ALC) and the role of funding policies: An evolving evidence base for Canada. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. September 2011. Accessed at: http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/commissioned-research-reports/0666-HC-Report-SUTHERLAND_final.pdf

[ii] Quality-Innovation-Collaboration: Strengthening Seniors Care Delivery in BC. BC Care Providers Association. September 2015. Accessed at: https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/BCCPA-White-Paper-QuIC-FINAL-2015.pdf

[iii] Exploring alternative level of care (ALC) and the role of funding policies: An evolving evidence base for Canada. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. September 2011. Accessed at: http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/commissioned-research-reports/0666-HC-Report-SUTHERLAND_final.pdf

[iv] Quality-Innovation-Collaboration: Strengthening Seniors Care Delivery in BC. BC Care Providers Association. September 2015. Accessed at: https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/BCCPA-White-Paper-QuIC-FINAL-2015.pdf

[v] Wait Time Alliance. 2015. Eliminating Code Gridlock in Canada’s Health Care System: 2015. Wait Time Alliance Report Card Accessed at: http://www.waittimealliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/EN-FINAL-2015-WTA-Report-Card.pdf

[vi] Canadian Medical Association. Doctors to leaders: Canadians want a Seniors Care Plan in election. August 2, 2015. Accessed at: http://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/doctors-to-leaders-canadians-want-a-seniors-care-plan-in-election-520419582.html

[vii] Wait Time Alliance. 2015. Eliminating Code Gridlock in Canada’s Health Care System: 2015. Wait Time Alliance Report Card Accessed at: http://www.waittimealliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/EN-FINAL-2015-WTA-Report-Card.pdf

[viii] McCloskey R, Jarrett P, Stewart C, Nicholson P. Alternate level of care patients in hospitals: What does dementia have to do with this? Can Geriatr J 2014;17(3):88–94.

[ix] Wait Time Alliance. 2015. Eliminating Code Gridlock in Canada’s Health Care System: 2015. Wait Time Alliance Report Card Accessed at: http://www.waittimealliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/EN-FINAL-2015-WTA-Report-Card.pdf

[x] NHS England. Delayed transfers of care statistics for England 2014/15. 2014/15 annual report. London: NHS England; 2015 May 29. Available: www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2013/04/2014-15-Delayed-Transfers-of-Care-Annual-Report.pdf

[xi] BC Office of the Seniors Advocate (2015) Monitoring Seniors Services. January 2016. Accessed at: http://www.seniorsadvocatebc.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/01/SA-MonitoringSeniorsServices-2015.pdf

[xii] Quality-Innovation-Collaboration: Strengthening Seniors Care Delivery in BC. BC Care Providers Association. September 2015. Accessed at: https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/BCCPA-White-Paper-QuIC-FINAL-2015.pdf