By Michael Kary

As highlighted by the “CareCanBeThere” media campaign, on January 24, 2017 the BC Care Providers Association (BCCPA) released a major new policy paper entitled Strengthening Seniors Care: A Made-in-BC Roadmap. As outlined in the paper, the province’s health system is still largely acute care oriented and not optimally designed to provide care for those with ongoing care needs, such as the chronically ill or the frail elderly. In order to address these challenges, Strengthening Seniors Care outlines 30 recommendations, focused on improving seniors’ quality of life, investing in health human resources, and renewing infrastructure, as well innovative new approaches to the delivery and funding of continuing care.

One such innovation discussed within Strengthening Seniors Care is the development of a new Care Credits Program. This project proposes that the BC Government allocate up to $2 million annually to provide seniors (or the family members that care for them) the option to direct their own care by selecting the service provider of their choice.[i]

As outlined in the paper, in Canada (including BC) the provision of subsidized continuing care is almost entirely in-kind, rather than in cash or vouchers (referred to herein as care credits). Under BC’s current system, co-payments for both home care and residential care services are fixed and the provincial government pays the residual costs of services supplied to subsidized seniors.[ii]

However, many European countries use a system of consumer directed care or care credits. Under a care credits program, instead of paying for continuing care on behalf of recipients, the government provides transfers to clients with which they can purchase services from a variety of potential providers. The amount of the transfers is is determined based on the individual’s care needs and ability to pay. While governments in countries that have care credit programs still play a critical role in regulating providers and ensuring they meet a minimum quality of care, they no longer contract with providers, who now engage clients directly. [iii]

As outlined in a 2012 C.D. Howe report, new funding models such as care credits are intended to be more reactive to clients’ needs by enhancing the ability of people to stay in their homes longer. In particular, financial and service flows for funding long-term care in France and Nordic countries are intended to give clients a greater say over their path of care. [iv]

The trend in many countries toward the use of care credits rather than providing services in-kind was motivated in part by the belief that more choice for clients and competition among providers would lead to efficiency gains in the system and promote greater independence.

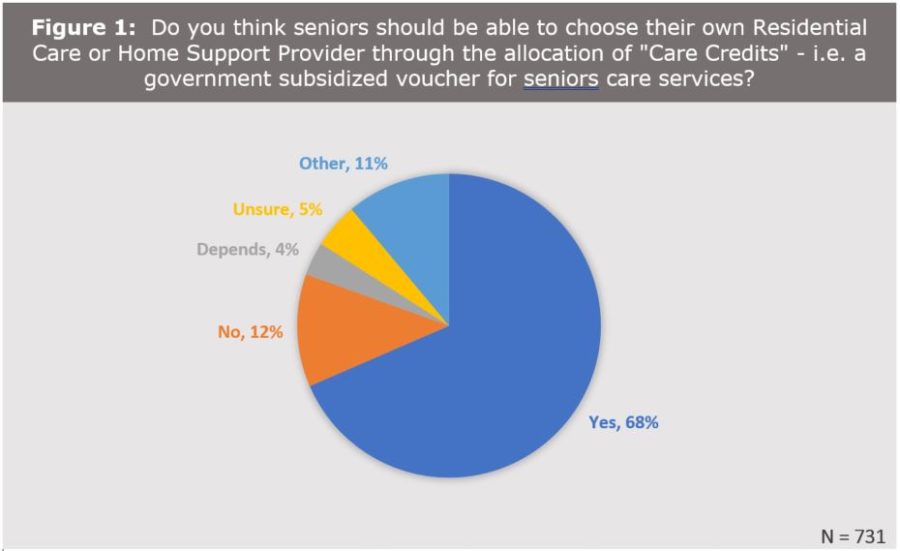

The idea of care credits or offering greater personal choice also seems to receive some broad public support. For example, as part of a 2016 survey of an earlier BCCPA paper, respondents were asked if they would support use of care credits for seniors to directly purchase continuing care services. Overall, the proposal received good support, with 68% indicating were in favour and only 12% against (see Figure 1).[v]

Although there are many potential benefits of care credits including increased choice, they may have some drawbacks as well. Such concerns include that providers will seek out clients with low-care needs relative to costs (i.e. cream-skimming) or the increased difficulty of governments to exercise a high level of control over their annual health budgets. Another potential drawback is that https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/medcare-img22.jpgistrative costs may increase, as the size of the subsidy would likely need to change over time to meet a client’s needs.[vi] In particular, any such program would have to appropriately assess the needs of the client on a regular basis and adjust the subsidy accordingly. Finally, among countries that have adopted a care credit program it is unclear whether efficiency gains have materialized, although providing greater choice generally has seemed to increase the reported satisfaction of clients who value being involved in decisions about their care. [vii]

One recent study from the UK shows that an experiment to introduce care credits into residential care has had limited success, after pilot projects showed poor uptake among seniors. In the pilots, the British government offered 20 local authorities the option to participate, whereby funding that would normally go to the care home went instead to the resident as a direct payment. The pilot projects initially offered direct payments only to existing residents, who may have been living in the care homes for years – however the majority declined to participate, feeling it would change their relationship with their provider. While it later became more common for incoming residents to be given the opportunity to take advantage of direct payments, of those who did avail themselves of the program, there was fairly widespread disappointment with the provider’s inability to offer any significant flexibility. [viii]

While care credits may have potential drawbacks, as noted earlier many countries have already implemented such a program or are currently introducing one. Australia, for example, is proceeding with the introduction of care credits, particularly in the home care sector. As of February 2017, citizens in that country will be able to receive funding directly and to choose the home care package of their choice.[ix] Australia is also exploring greater consumer directed care models in residential care.

Along with health care, the use of credits or vouchers are also used widely for other social programs, particularly education where the funding follows the student, not the school or institution. Under such a program if someone chooses to go to a private school, a smaller allocation (compared to public schools) will be paid directly to the authorized private provider. Since 1992, Sweden has had universal voucher system where grants follow the child, and a voucher can be used to pay tuition in a private, independent, or non-denominational school.

It should also be noted that similar programs already exist in British Columbia for individuals with physical disabilities and development delays. One such program is offered by Community Living B.C. (CLBC), which allows their clients the opportunity to select the care provider of their choice. CLBC’s Individualized Funding program, for example, assists people with disabilities to participate in activities and live in their community by allowing individuals (and their families) to access services from a provider of their choice.[x] If such a program can be offered to people with development disabilities or delays, why could it not be potentially offered to frail and elderly seniors?

In conclusion, based on the available information, the BCCPA believes the use of care credits should also be explored further for adoption in the province. As outlined in Strengthening Seniors Care: A Made-in-BC Roadmap, the BCCPA recommends that the BC government allocate up to $2 million per year to launch a new Care Credits program that provides seniors (or family members that care for them) the option to select the service provider of their choice.

The BCCPA recommends that the Care Credit program be introduced initially in the home health sector, and its use in the residential care sector should be studied before implementing on a wider scale. While the BCCPA recognizes that a care credit program may not be appropriate or desired by all frail or elderly seniors, it is nonetheless a concept that should be explored further to provide seniors and their families greater choice and say in their overall care.

END NOTES

[i] BCCPA. Strengthening Seniors Care: A Made-in-BC Roadmap. January 2017. Accessed at: https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/BCCPA_Roadmap_Full_Jan2017.pdf.

[ii] Long-Term Care for the Elderly: Challenges and Policy Options. CD Howe Institute. Commentary 367. Ake Blomqvist and Colin Busby. November 2012. Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Commentary_367_0.pdf

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] BCCPA. Strengthening Seniors Care: A Made-in-BC Roadmap. January 2017. Accessed at: https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/BCCPA_Roadmap_Full_Jan2017.pdf.

[vi] Long-Term Care for the Elderly: Challenges and Policy Options. CD Howe Institute. Commentary 367. Ake Blomqvist and Colin Busby. November 2012. Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Commentary_367_0.pdf

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Challenges of CDC in residential emerge in UK pilots. Australian Ageing Agenda News. Darragh O’Keeffe. July 8, 2016. Accessed at: http://www.australianageingagenda.com.au/2016/07/08/challenges-cdc-residential-emerge-uk-pilots/

[ix] Australian Government: Department of Health. Consumer Directed Care Fact Sheet. October 14, 2016. Accessed at: https://agedcare.health.gov.au/programs/home-care/consumer-directed-care.

[x]Community Living BC, Individualized Funding, CLBC Fact Sheet. Accessed at:

http://www.communitylivingbc.ca/wp-content/uploads/Individualized-Funding-Fact-Sheet.pdf